I appreciated Bart Elmore’s recent writeup in The Conversation about the prevalence of herbicides in our food supply. The article covers the two big headliner herbicides Dicamba and Glyphosate, as well as a resurgence of other herbicides that had been sidelined for the last twenty years.

The basic insight is that herbicide use is on the rise, but not just a little. It is way, way up. Farming has backed itself into a corner, and it is attempting to spray its way out.

Genetically modified crops like corn, soybeans, and cotton were introduced commercially in the mid 1990s. Gene modification made these crops resistant to Glyphosate (Round Up), so a field could be sprayed killing every other plant except the ones with the specific genetic alteration. The promise from Monsanto (now Bayer) and other advocates was that they would allow farmers to spray less total herbicides. So how did that work out?

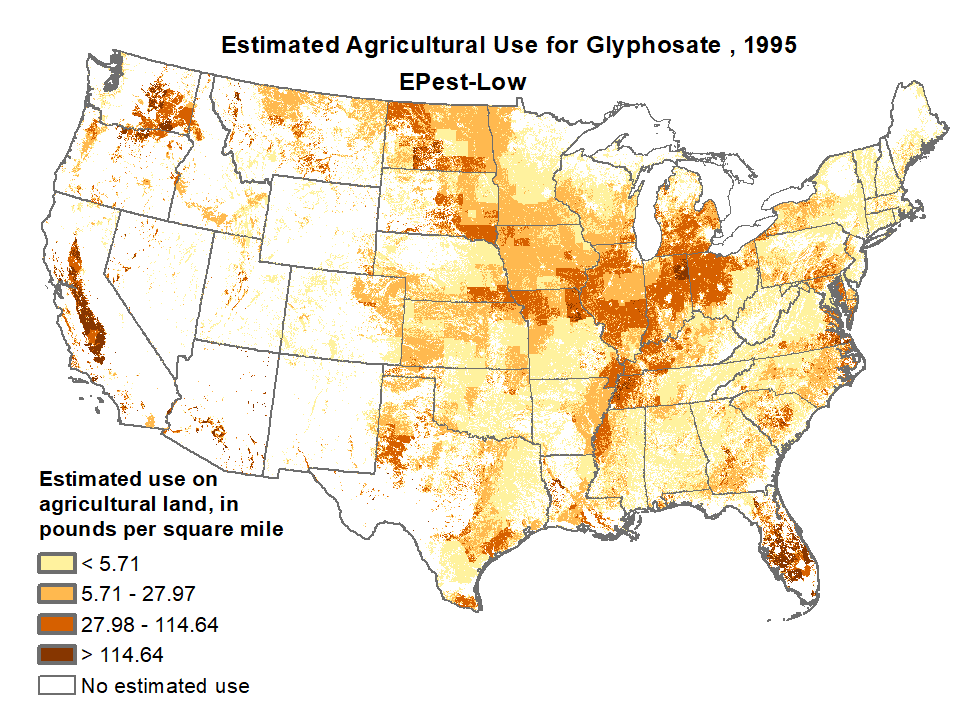

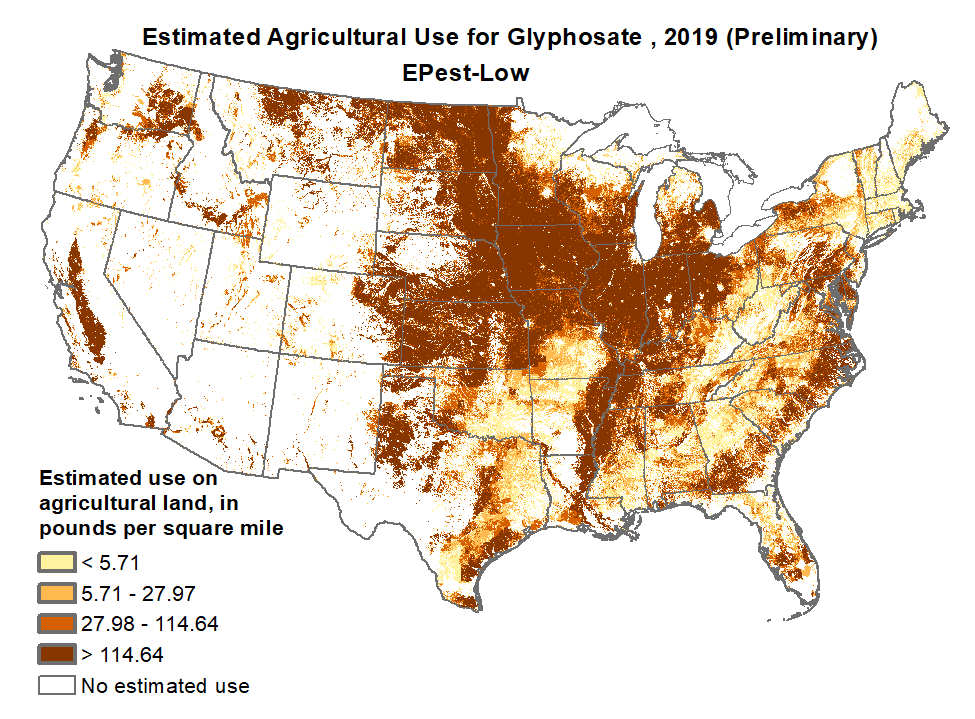

Use the slider on the image to compare glyphosate use per square mile in 1995 versus 2019.

The heavy applications of herbicides, rather than eliminating weeds, eventually selected for super-resistant weeds. So for instance, palmer amaranth weeds have adapted to shrug off direct hits with glyphosate. Farmers, in order to bring in a good crop, felt the need to add more and more herbicides to keep the weeds knocked back. Compared to the original GMO seeds that were compatible with glyphosate, the newest GMO crop seeds are being engineered to resist a cocktail of five different herbicides just to stay ahead of the weeds.

For all the talk from those who stand to make money from selling GMO seeds and herbicides, for all their assurances that they are solving the world’s food problems, it really makes me wonder. If in just ten years weeds were able to evolve end-runs around our herbicides, what makes us think that weeds won’t jump past a blend of five herbicides in another few decades. How much time does conventional crop agriculture really have left? And then what do we do? Start spraying a ten- or fifteen-way blend of herbicides? Why can’t we pursue a different kind of agriculture, one that isn’t oriented toward the reductionism of mono-cropped fields where chemical control is our only tool?

Sure, our farm is an Organic farm, so we have a natural bias against herbicides. I’ll be the first to admit that Organic requires a purist approach that isn’t right for everyone. But even if we allow that there will always be some large portion of the market that keeps using herbicides and pesticides, can’t we find a way to back these things down? Must we continue to fall for the same old tale from the tech companies and seed companies? They tell us that, sure, the current technology is screwed up, but the next version will fix everything. Will it?

If we want to have a hope of feeding ourselves into the future, we had better learn to grow food using methods that take into account the complexity of the natural world. Farming can’t be sustainably modeled on systems of chemical and biological warfare. This just proliferates problems faster than we can develop solutions.

The big, evil, pesticide-loving companies aren’t the only villains here. We’re all the perpetrators, we’re all complicit. To the extent that we choose cheap over fairly-priced, the extent that we choose convenient over homemade, we are collectively signaling to the market that we accept the herbicide compromises necessary to create an abundance of questionably healthy food.

These are collective action problems, and I don’t pretend to know how to change American culture. Our whole social and economic system has been built around the premise that the greatest public good is in providing the cheapest possible calories to a population that is as far removed from their food production as possible. And I would add that our enormous healthcare and pharmaceutical systems are built around the assumption that there is money to be made in treating a population debilitated by our food system. Cheap, undifferentiated, commoditized food is the fuel that runs America.

If I could encourage one habit among everyone, it would be to grow some food. Whether that would be a backyard garden, or a spot in a community garden, or a few potted vegetables on the front steps, the scale is immaterial. The important thing would for people to be involved in their own food production year after year. This would never save any money – discount produce would always be cheaper in the grocery stores. Rather, this would teach us all things.

If we all understood the challenges in growing food, it would at least make us understand the pressure to use herbicides, fungicides, and pesticides. After watching cabbage moths eat your broccoli, you might start thinking about reaching for that spray bottle. The “bad guys” wouldn’t be straw men. Even if we don’t agree with the folks promoting herbicide use, it would help us to understand them. Struggling together on a problem is better than struggling against each other to solve a problem.

The other benefit from our personal involvement in food and farming would be appreciation. We’d understand the effort required in bringing a meal to the table. And we’d start to assign more value to our food. We’d focus on taste and quality. We’d understand seasonal fluctuations. We’d be more careful about waste. If we all valued our food, I think we could begin to make fundamental changes that could ripple through society.

2 thoughts on “Herbicide Without End”

Absolutely appreciating your efforts and posts. We started a garden a few years ago. It takes a few seasons of trial and error staying chemical free. Specified areas of our small yard for the bees. Trying hydroponics for the first time this winter in our basement. Patience and understanding good for the earth, good for all of us. Keep fighting the good fight!

That’s great Michele. I agree with the bit about trial and error. We’re always in that trial and error cycle, but there’s so much that can come out of the experience of observation, learning, and adapting. Keep up the good work.