The English language has a history of a highly specialized vocabulary for animals. We have words for specific types of animals (“herd”, “flock”, “pride”, or “gaggle”). We have words that differentiate by gender (“buck” vs “doe” or “dog” vs “bitch”). We have words to indicate age (“colt”, “kit”, or “kid”) and general body condition (“nag” or “breaker”).

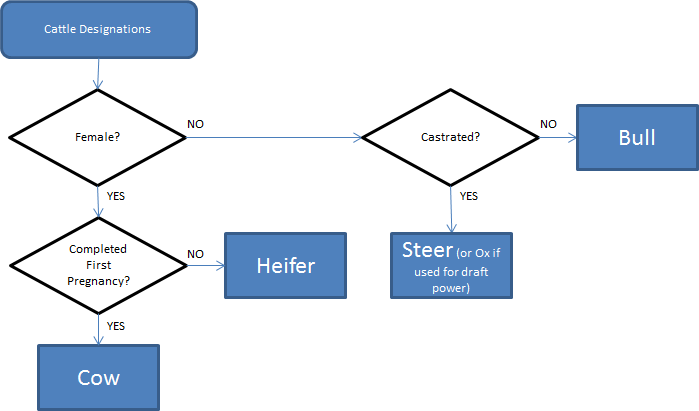

When people talk to us about our livestock, there is often some awkwardness discernible just because the specialized language isn’t universally familiar. So here is a general overview of the bovine nomenclature.

Perhaps the biggest confusion is between “cow” and “cattle”. Often people will refer to an indeterminate group of cattle as cows. To be technically correct, the species as a whole are cattle. So if you see a herd in a pasture and if you haven’t had a chance to check what’s under their tails and between their legs, you should refer to them as cattle. Cows are female cattle that have had their first calf. Dictionaries have acceded to the popular misuse of the word cow. Merriam-Webster’s second definition is “a domestic bovine animal regardless of sex or age“, The OED allows “(loosely) a domestic bovine animal, regardless of sex or age“. Among farmers the word cow is always used in its most literal, technical sense. This is probably akin to the distinction masons make between cement, concrete, and mortar: there are important differences between the three, but they understand even when their customers mistakenly request for a “cement” sidewalk.

Farmers and ranchers have additional layers of terminology to describe the different ages, sizes, and conditions of cattle. The terms get more complicated, as some are regionally defined and some are used differently for beef and dairy cattle. Commonly used terms include the following: calf, weaner, yearling, stocker, finisher, springer, fresh, dry, or broken-mouth. Then there are terms to describe their potential for butchering: bob, vealer, lean, light, finished, breaker, boner, utility, or canner. There are others to describe specific physical conditions, such as stag or freemartin. And there are archaic and obsolete terms you might find in older books: cow-brute, kine, bullock, or neat. None of these lists are comprehensive.

Unless you deal regularly with cattle, we don’t judge you harshly for using the wrong language. If you ask to order a side of beef from a cow, we’ll understand that what you really want is beef from a finished steer. We know you just care what it tastes like, not what it is called. But if you want ag cred, you’ve got to use the right words.